One shortcut to following the global coffee scene is to track the movements of Tim Styles, such is the Australian barista’s knack for turning up at seminal shops at the right time. He’s worked stints at Ray Cafe in Melbourne, Joe the Art of Coffee in New York, Flat White in London, Intelligentsia in Venice (California) and Penny University, the pop-up brew bar in London’s Shoreditch which popped down on the 30th of July.

One shortcut to following the global coffee scene is to track the movements of Tim Styles, such is the Australian barista’s knack for turning up at seminal shops at the right time. He’s worked stints at Ray Cafe in Melbourne, Joe the Art of Coffee in New York, Flat White in London, Intelligentsia in Venice (California) and Penny University, the pop-up brew bar in London’s Shoreditch which popped down on the 30th of July.

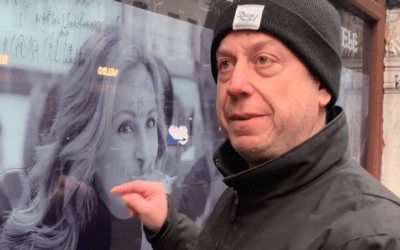

His chosen name and equally groovy occupation notwithstanding, Styles (né Williams) has yet to win a following of barista groupies, if said species truly exists, perhaps because he won’t act the rockstar part. The only smashing down he cares to do is of barriers between the customer and the server. Elegant, perceptive and meticulous in his approach to coffee preparation and service, he, like Tobias Cockerill and Square Mile Coffee‘s James Hoffmann, his Penny University colleagues, is more a barista in the sommelier mould, minus the stuffiness. The soft-spoken Styles is macho deficient and he’s “totally okay with that”.

Next week Styles turns 29, which, in barista years, is the equivalent of 58. When he started in the biz it was so long ago he wasn’t even using the term barista yet. His job was that of “coffeemaker” at the Bratwurst Shop in Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Market, preparing 800-1000 barely drinkable coffees per day in a busy deli packed as tightly as, well, a bratwurst. Hemmed into the corner by the 130-kilo (287 lb) Korean man who worked beside him, Styles took to leaning on one foot and unwittingly kicking off the shoe from the other. At Penny University he’s worn tightly laced boots, rather than his preferred Vans or Cloggs, to control a tic he’s never managed to – sorry – kick.

The first great coffee of Styles’ life was prepared at Ray Cafe by barista Alex Anderson, who would later work in London at Flat White. Too intimidated to linger for long at what was then an ultra-cool bastion of Melbourne artists and musicians, Styles did not take his first sip of latte until he’d stepped outside. “I was blown away”, he recalls, adding that the surface of Anderson’s steamed milk “looked like white glass” (no bubbles).

Styles later landed a barista job at Ray Cafe and was blown away once more, this time “by how little I knew compared with what I thought I knew”. He stayed there for two years, working night jobs all the while, and, with more confidence than money to his name, travelled to London (via New York) in September 2006 without a return ticket. Upon clearing customs he took the tube from Heathrow to Piccadilly and walked to Flat White, a rite of passage for Antipodean arrivals. “Flat White was the mecca for coffee”, he says. “No one touched them”. Styles stuck around Flat White for six months and paid close attention not only to the preparation of the coffee but also to the dynamics of the queue and customer involvement.

“Tim takes a huge amount of learning from each cafe experience”, notes Hoffmann, the co-patron of Penny University and the 2007 World Barista Champion. “He also has the wisdom to adapt his approach if the concept is very different to what he was doing before”.

Styles was increasingly intrigued by coffee shops which put the focus on their baristas and let them take control of the experience. At the Intellgentsia coffee bar in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles he observed how each customer was effectively met at the front of the queue by a person with a portafilter in his hand and a grinder at the ready. Moving along the counter from right to left the customer enjoyed easy access and interaction with those preparing his or her order. At the Intelligentsia in Venice, where Styles worked as a consultant at the time of its opening, the bar was replaced by four stations where customers would have a one-to-one interface with a barista.

Penny University, with only six seats, two baristas and no espresso, slowed that interface to a drip. As the acoustic counterparts to heavy-metal espresso machines, the pour-over and siphon brewers freed the baristas and customers to converse with each other in relative calm.

Styles obsessed about the operational details that would allow Penny U baristas to take control of the situation and share their excitement about the coffees without talking down to customers. To take one example, small water glasses were chosen so that the baristas would be refilling them often and subtly reminding customers they were being looked after.

Styles obsessed about the operational details that would allow Penny U baristas to take control of the situation and share their excitement about the coffees without talking down to customers. To take one example, small water glasses were chosen so that the baristas would be refilling them often and subtly reminding customers they were being looked after.

Prior to its opening Styles predicted Penny U would confront a walkout rate of about 30 percent. The English were not accustomed to drinking filter coffee in cafés and they surely never encountered any who refused their requests for sugar and milk. Londoners, he reasoned, were introspective and difficult, unlike the forward-thinking, open-minded free spirits of Venice.

Prior to its opening Styles predicted Penny U would confront a walkout rate of about 30 percent. The English were not accustomed to drinking filter coffee in cafés and they surely never encountered any who refused their requests for sugar and milk. Londoners, he reasoned, were introspective and difficult, unlike the forward-thinking, open-minded free spirits of Venice.

He was wrong. The walkout rate was negligible. Among some 2000 served there were only four requests for milk. This time it was London that blew the one-shoed barista away.

0 Comments